Saints and Sunshine

And why geese fear Remembrance Day

So what’s the connection between a Roman soldier, roasted chestnuts and a nice stretch of November sun?

The answer is Saint Martin, and he’s also responsible for the death of many prophetic geese, cross-dressing Estonian children and some Polish competitive croissant baking.

It’s funny how the simple phrase “it turned out nice again” can lead down an historical and mythological rabbit hole and pose an as yet unanswered question about the timing of Armistice Day.

This week’s despatch is about a deep connection to the land and the changing of the seasons in our little part of Portugal, but first I suppose this all needs a little unpacking.

“It turned out nice again,” I said to Richard during our trip to the Algarve last Thursday.

“It’s Verão de São Martinho ,” he replied – St. Martin's Summer – “you should be eating chestnuts,” and so began a deep dive into thousands of years of myth, religious appropriation and meteorology.

It was November 11th – Martinmas, or Martlemass – and it’s a big deal across Europe marking a period of change from autumn into winter and as an ancient inspiration for some modern celebrations.

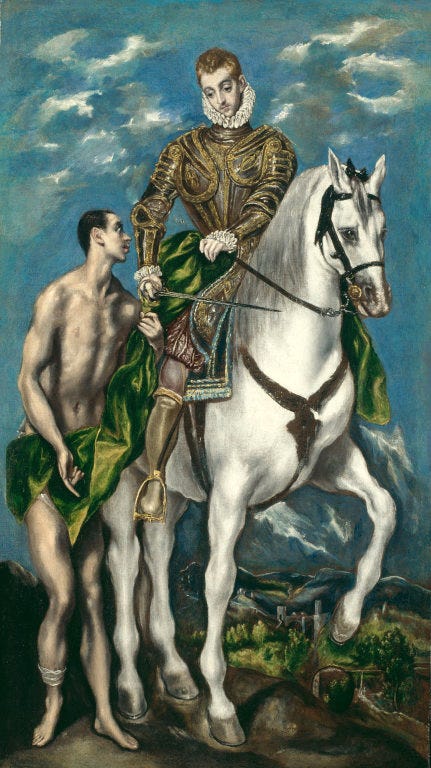

Martin (while he was still just Martin) was born it what is now Hungary in AD 316 and while living in northern Italy joined the Roman army.

The “God-fearing” man was heading back home from a battle in France on a cold and stormy day when he came across a beggar (possibly drunk) who asked him for food.

He didn’t have any, but instead took his Roman robe and cut it in half with his sword to share with the man.

The rain stopped, the clouds cleared and the sun shone – it was “as if God had forgotten it was autumn and summer returned for three days” – and it was known as the miracle of St. Martin.

The soldier is then said to have given up the army for religion and dedicated his life to spreading Christianity throughout Gaul, founding a church and becoming Saint Martin of Tours in modern day France.

The day of his death in AD 397 was November 11th and St. Martin’s story spread across Europe and beyond.

Christopher Columbus spotted land in the Caribbean on that day in 1493 and named it Saint Martin’s Island.

Martin became the patron saint of tailors, knights, soldiers, beggars...and wine producers, and even got a hat tip in Shakespeare’s Henry VI.

Tailors, I get; same with knights/soldiers and of course beggars, but unless the new owner of half a robe was actually drunk, the last bit is a stretch...unless you go the religious appropriation route.

Why is Christmas Day on December 25th? Why is Easter on a different day every year? Where does Yule-tide come from?

They’re all questions worthy of their own rabbit hole, but the point is a lot of religious festivals are based on far more ancient pagan rituals merged into Christianity. Things can get levered into to a story to suit the narrative.

And at this time of year all sorts of northern hemisphere traditions combine around the theme of change from light to darkness, from warm into cold.

It’s the time of Halloween, Thanksgiving, of bonfire nights and lantern processions – of slaughtering fattened animals for winter and of celebrating the harvest of what the earth can provide for us humans.

In Portugal (as elsewhere) this is the time for roasting chestnuts – stalls are set up all over the country from small towns to the back streets of Lisbon.

Chestnuts were a staple food in Portugal before the discoveries brought potatoes, rice and pasta.

They’re full of vitamins, minerals and carbs, but low in fat and clean the blood of acids produced by eating red meat.

It’s also the first time the year’s wine has fermented enough to be tasted – and many countries try out their early vintage on St Martin’s Day. A retrospective saint perhaps?

That happens in Portugal but there’s also água-pé here. The literal translation is “foot water” and it’s an alcoholic drink made by adding water to the solids left at the bottom (or the foot) of the barrel after the grape juice has been fermented into wine.

“É dia de São Martinho; “It is St. Martin's Day,

comem-se castanhas, prova-se o vinho.” we'll eat chestnuts, we'll taste the wine.”

But what about the weather?

We’ve been enjoying Verão de São Martinho for a week now: beautiful warm and sunny weather which Portugal often experiences in mid-November after the first Atlantic storm.

Our climate is linked to the Azores High – a sub-tropical anticyclone which keeps the Sahara hot and dry, provides summer heatwaves here and helps create hurricanes in North America.

A little wobble of high pressure during the transition to winter is the meteorological explanation for St. Martin's Summer, or what’s known as an Indian Summer in the UK and US.

Across Europe St. Martin's Day started in France, but different countries took traditions and beliefs in different directions, and that’s where the prophetic geese come in.

St. Martin apparently hid in a goose pen while trying to avoid being ordained as a bishop, but the racket they made gave him away.

Now geese fear Martinmas as much as turkeys are terrified of Christmas and the threat of Thanksgiving.

- In Hungary they say if the geese waddle on ice on Martinmas it will paddle in water at Christmas – predicting an icy November will be followed by a mild December. That’s if there are any geese left to make a prediction: the other Hungarian expression is if you don’t eat goose on November 11th you will be hungry all winter.

- The Czechs get through a lot of geese too, and in southern Sweden they mark Mårtensafton, with svartsoppa, or goose blood soup.

- But it’s probably more about preparing for winter as fattened piggies also don’t do well. “Every pig gets it’s St Martin,” is a euphemism in Spain, France and in Britain for their Martinmas slaughtering. In Switzerland it’s pigs and shots...for five hours.

- Bonfires and lantern processions mark Martinsfeuer (Martin’s eve) in Germany and Austria and kids go from house to house singing songs and getting candy. Note the Halloween trick-or-treating and Bonfire Night connection.

- Maltesers have less sugar...as children in Malta are given a bag full of nuts, figs and chestnuts known as St Martin’s Bag, and in Estonia children dress as men while going door to door asking for sweets.

- In Wales the Cwm Annwn spectral hounds who escort souls to the underworld have a “wild hunt” night on Martinmas where they are allowed to search for criminals and villains. There’s superstition about owls hooting and shooting stars. It’s another pagan link to Halloween.

- In Poland there’s competitive almond croissants baking; and in Ireland they kill cockerels and spread their blood around the house.

- In Croatia they go big on the young wine tasting, appointing a “wine bishop” to give a blessing and choose a godfather for the year’s vintage; in Slovenia it’s similar but with a wine Queen; and in the CzechRepublic they start drinking the new wines at 11.11am. Now that’s a significant time that poses a question...

In the UK it’s less about St Martin and more about Remembrance, but can it be pure coincidence that Armistice Day was chosen as the 11th hour of the 11th day of the 11th month?

It’s been an important day for millennia – and someone chose that time with these big ideas of change in mind.

I’d love to know who...